Slob Culture: How America Learned to Dress Like It Gave Up

There was a time when leaving the house required a minor performance. Shoes were tied, while put-together outfits implied purpose. Even rebellion had a uniform, leather jackets, ripped jeans, subcultural codes you had to earn. Today, the dominant aesthetic of American life is something else entirely: surrender. Welcome to slob culture.

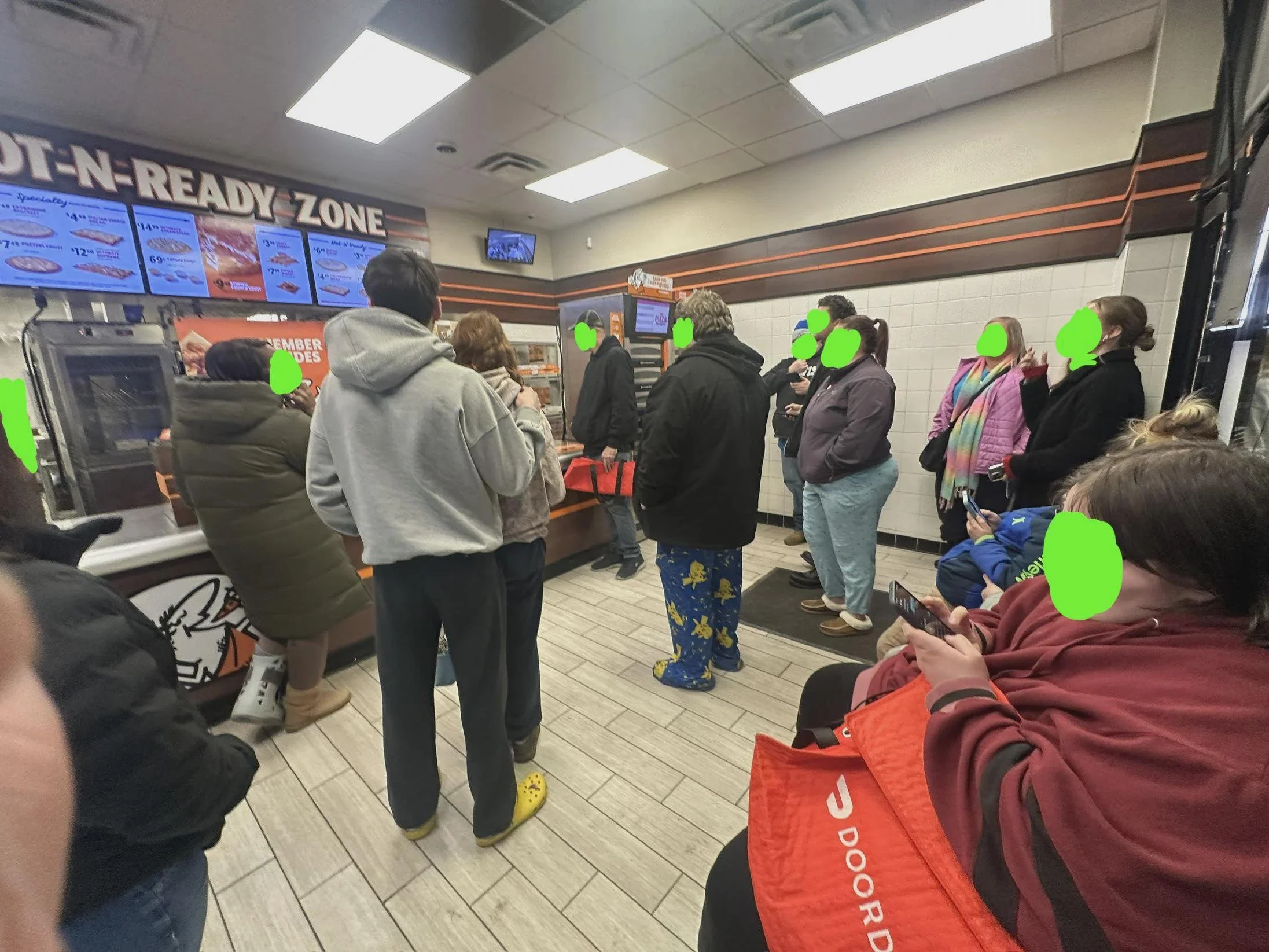

Slob culture isn’t just about comfort. Comfort has always existed. It’s about public indifference, an aesthetic of emotional disengagement rendered in stretched-out sweatpants, Crocs in all weather, pajama bottoms all day, and T-shirts that express fatigue. It’s not accidental, but systemic.

The rise of slob fashion tracks perfectly with the collapse of shared public standards. As work-from-home blurred the line between private and public life, the idea of “getting dressed” became optional, then suspicious, then vaguely difficult. To dress well now is often read as a statement—of class, aspiration, or arrogance—rather than simple self-respect. The safest move is to look like you didn’t try at all.

Athleisure accelerated the trend by pretending it was about health. Leggings became pants. Hoodies became office wear. Sneakers designed for no particular sport replaced shoes that once suggested where you were going or what you were doing. Fashion stopped pointing outward toward the world and turned inward, toward the couch.

Slob culture pairs neatly with algorithmic life. When your primary audience is a screen, your body becomes a background object. From the waist up matters for Zoom. From the neck up matters for selfies. The rest dissolves into fabric designed to disappear. Fashion becomes less about presence and more about minimizing friction between naps, notifications, and food delivery.

There’s also an economic honesty to it. Many Americans are tired, overworked, and underpaid. Slob culture is a visible symptom of burnout. It says: I am conserving energy. I am opting out of performance. I no longer believe effort will be rewarded. In that sense, it’s less laziness than resignation.

But resignation has consequences. When no one dresses for public life, public life thins out. Restaurants feel like food courts. Airports feel like waiting rooms. Even cultural events flatten out. No contrast, no occasion, no signal that something matters more than scrolling. Fashion used to create small rituals of meaning. You dressed differently for dates, funerals, interviews, nights out, days off. Slob culture collapses those distinctions into one endless Sunday afternoon. The result is not freedom, but monotony.

Fashion once revolved around the silhouette—the disciplined shaping of the body in relation to fabric. Slob culture dissolves the body entirely. Oversized hoodies, shapeless joggers, and elastic-waist everything erase proportion, posture, and tension. The body is no longer styled; it’s hidden. This isn’t liberation, but visual anesthesia. By removing structure, fashion forfeits its ability to create meaning. There is no line to follow, no contrast to register, no decision to read. When everything is loose, nothing is expressive. The wearer disappears into volume.

The idea that effort equals elitism is a contemporary myth, one that conveniently excuses mediocrity while luxury brands profit from selling engineered sloppiness at inflated prices. The wealthy now cosplay indifference. The poor are told it’s freedom.

Modern American fashion is saturated with irony: ugly sneakers, deliberately awkward fits, clothes that signal knowing detachment. But irony without opposition becomes inertia. When everyone is in on the joke, the joke stops being funny. Slob culture is irony that’s forgotten its punchline. It no longer critiques anything; it simply persists, unexamined, as default behavior. What began as anti-fashion has calcified into uniform.

Perhaps the most corrosive aspect of slob culture is its erasure of context. Clothes once marked transitions: home to street, rest to labor, private self to public role. Now the same garments function everywhere, which means nowhere feels distinct. Pajamas at the airport. Gym clothes at dinner. Loungewear at work. The message isn’t comfort but disengagement, a refusal to acknowledge space, occasion, or audience. Not rebellion, just flattening.

Fashion requires risk, of looking foolish, of trying too hard, of missing the mark. Slob culture avoids risk entirely. It opts for the safest possible aesthetic: neutral, soft, anonymous. Nothing to critique, nothing to admire. This is why so much contemporary fashion feels lifeless. Not because it’s casual, but because it’s incurious. It asks nothing of the wearer and offers nothing in return.

What slob culture ultimately erodes is not elegance, but intention. Dressing well is a form of thinking in public. It signals that choices were made, that the body was considered, that the day mattered enough to warrant attention. When that disappears, fashion stops being a conversation and becomes background noise. Slob culture doesn’t challenge power. It doesn’t democratize beauty. It doesn’t free the body. It simply reflects a society that has given up on signaling meaning through appearance, and mistakes that surrender for progress.

One of the quieter consequences of slob culture is how it misleads immigrants. For many of them, clothing is not trivial but a code. Dress has historically been a way to signal seriousness, respectability, readiness to participate. But modern America sends a corrupted signal.

What immigrants often encounter isn’t a society dressed down for leisure, but a society that has normalized aesthetic indifference as cultural fluency. To blend in, to avoid standing out, to appear modern or “American,” many adopt what they see as the prevailing look: oversized hoodies, athletic wear worn nowhere near athletics, deliberately unkempt silhouettes. Not because it reflects their values, but because it appears to reflect belonging. This is not imitation born of laziness; it’s mimicry under uncertainty.

In many parts of the world, dressing well is still understood as a form of respect, for the public sphere, for others, for oneself. Upon arrival, that instinct collides with an American visual culture that treats effort with suspicion. The newcomer learns quickly: polish reads as naïveté, formality as misreading the room. Sloppiness, paradoxically, reads as cultural literacy.

Slob culture functions as a false passport, one that promises invisibility through sameness. Immigrants dress down not to rebel, but to disappear into the crowd. The tragedy is that the crowd itself has abandoned distinction. What they are assimilating into is not confidence, but confusion. Not freedom, but the absence of standards. A culture so afraid of hierarchy that it refuses even benign forms of discernment, like fit, proportion, cleanliness, intention.

And so the cycle continues: newcomers absorb the aesthetic signals of exhaustion and detachment, reinforcing the very norms that misled them. Slob culture spreads not because it is persuasive, but because it is ambient.

The irony is sharp. Those who once dressed carefully to be taken seriously now learn that seriousness is optional, even suspect. Meanwhile, those secure enough to ignore appearances frame their indifference as authenticity, while others copy it as survival strategy. This is how a culture exports its worst habits as ideals. Slob culture doesn’t merely flatten class or erase aspiration; it scrambles the meaning of effort itself. It teaches newcomers that to belong, one must look like nothing in particular, aim for no visual coherence, and treat the public sphere as an extension of the couch. That isn’t inclusion, it’s mis-education.